Mutiny!

The following post is a review of Kester Brewin’s book, Mutiny! Why We Love Pirates, and How They Can Save Us, available in paperback and e-book format.

In the 7th grade I carefully crafted a handful of pirate’s licenses for myself and some friends. Crudely designed in Microsoft Paint, these licenses permitted us to speak like pirates and to do all things pirate related. They featured a prominent skull and crossbones, the permissions granted us as pirates, as well as our pirate names. I was Peg Leg Pete. Very official. I’m not entirely sure what sparked our interest in pirates (full disclosure: it could very well have been a song by The Aquabats). For us, this was a way to be weird and have our own club. We joked about rum and parrots and booty and pillaging. That is what pirates were to us. They were mean and nasty men with a penchant for robbery, violence, treasure and growing ratty beards. This idea of pirates as fearsome dregs of society is reinforced through the stories told about them.

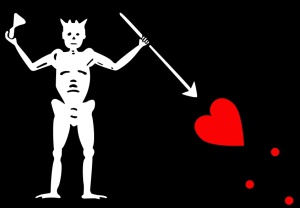

In Mutiny! Why We Love Pirates, And How They Can Save Us, Kester Brewin examines our cultural fascination with pirates alongside their counter-cultural history, while peering into both the psychological and the theological. Brewin offers a divergent image of the pirate, and traces the legacy of piracy into the 21st century. The pirate and the skulls and crossbones have become a tame, cute, and often ironic cultural symbol that has been neutered of its radical and anti-imperialist sentiments. Brewin aims to recast these symbols and what they stand for in light of the injustice, social and economic inequality, oppression and corporate greed that inhabit our realities and beg for ‘unblocking’ and a cleared path for all. Brewin juxtaposes the spirit of piracy alongside ways in which our world is increasingly becoming privatized, manipulated and ‘blocked’ by systems of power. Everything from media to the government, the earth and its resources, and even religion falls victim to such blocking. The work of ‘unblocking’––creating a space for free movement, unhindered by systems of power––is the work of pirate activity, and Brewin shows that this is also the work of Jesus. Within this paradigm, the term mutiny serves as a new metaphor for rebellion, counter-culture, anti-consumerism, non-conformity, and the challenge of the status quo as functions of Jesus followers.

Pirates date back to long before the Atlantic pirates and ol’ Jack Sparrow. Brewin shows that since as early as second century CE pirates have stood up against the powerful, citing opposition to the Roman Empire’s attempts at extending their sovereignty to include the prior unowned and un-ownable oceans.

Rome went to war against pirates because pirates were threatening their claim to ownership, not just of the natural resources in the lands that they had dominated, but of the routes by which these resources could be moved, and thus transferred into riches. Pirates thus stood for the Romans not as simply a nuisance, committing petty theft on the seas, but as a threat to the values and principles that underpinned their empire. It was they who wrote into their laws that pirates were hostis humanis generis – the ‘enemies of all mankind.’

“Pirates were the antithesis of everything that Rome worked for: respect for authority, hard work, ordered trade and deference to a divinely appointed elite. From early history we see the designation ‘pirate’ going beyond robbery to suggest a wider menace that could undermine the values of empire.”

This wider understanding of piracy––interference contextualized inside of unjust systems of power and ownership––is the paradigm by which mutiny can save us. But who is the us in this equation? Here is where Brewin’s redemption of the pirate mystique differs from our cultural hand-me-down understanding of pirates: pirate interference is to unblock power are for the common good rather than interference for the sake of robbery and greed. The latter understanding reinforces the imperial designation of the pirate as a threat to order, civility, and peace; it is demonizing of those who hurl a challenge to power. “It wasn’t their thievery that was so heinous, so unutterably villainous, but their self-determination and refusal to be governed.” It was their refusal to play by the rules of empire. The us invites us to reflect on our power and act for the common good, partnering with and transferring power to the marginalized, voiceless, and powerless. The pirate manipulates and exposes the tools of the powerful for the sake of those without power. This is an act that is truly threatening, and one we see employed by Jesus throughout Gospels.

“This, then, is what we can take ‘pirate’ to mean: one who emerges to defend the commons wherever homes, cultures or economies become ‘blocked’ by the rich. Be it land that is being enclosed, or monopolies that are excluding and censoring, or wealth that has been hoarded, blockages to what should be shared freely and equitably create the conditions in which pirates will be found.”

It is through this lens that Jesus can be cast in the same vein as the pirate.

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Brewin comments that this scene from Luke 4, in which Jesus quotes from Isaiah, is a “classic pirate text, full of unblocking and the breaking of oppressive practices.” The message of Jesus, he goes on to say, “is not centered around time spent in dedicated worship and contemplation in the temple, but about social justice and release from captivity.” How does this transform the way we understand and interpret Jesus vis-a-vis social structures and empire? How does this change the way we imitate Jesus, or the way we inhabit the Christian faith?

Throughout Mutiny!, Brewin stokes the radical imagination with story and commentary, and invites us to reassess our relationships with each other, our own selves, our work, our leisure, our faith traditions, and ultimately, to the structures of empire. Brewin offers a creative and exciting new invitation into liberation theology. His “dark reading” of the prodigal son alone is worth the price of the book. To be sure, he pulls no punches while calling into question the theology and systems of power that have led to blockages in the radical movement that Jesus inspired, but he manages to balance playfulness and critique in a manner that is both accessible and challenging.

If you’ve read Mutiny!, what were your reactions? How has it influenced or changed your thinking?

Visit Kester Brewin’s website:

Listen to Kester Brewin on the upcoming Homebrewed Christianity Live Podcast on October 25.

I was sent a free copy of this book to review by the Speakeasy blogging book review network. My opinions are my own. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.